Home-based workers produce goods and services for local, domestic or global markets. They have always been isolated and invisible, but the COVID-19 crisis has created new challenges that have left millions in desperate circumstances.

Subcontracted homeworkers severed from global supply chains

Since the start of the pandemic, homeworkers who are subcontracted by global supply chains have either not received new orders or their regular orders have not been renewed.

In South Asia and Southeast Asia, where millions of women do piecework for national and international brands, work began to fall off in January as fears of the virus spread. The workers get most of their raw materials from China and, early in the pandemic, they were unable to get these supplies or had to pay more. This affected those who produce garments as well as those who assemble electronics, games and other products.

In India as elsewhere in Asia, an abrupt lockdown meant that there was no time to bring in material to do any work, and home-based workers are not included in emergency relief packages in most countries in the region (though Cambodia, Laos and Nepal are offering reduced electricity bills to poor households).

The exception is Thailand. Here, WIEGO Network members and partners engaged the government — with support from alliances and the media — and called for emergency measures. The government announced a package that includes cash grants of 5,000 Bhat (about 50% of minimum wage) to help support Thailand’s nearly 3.7 million home-based workers; however it is possible not all will qualify. HomeNet Thailand and the Federation of Informal Workers are helping workers apply. Lower interest loans are also part of the package.

HomeNet South Asia (HNSA) and HomeNet South East Asia (HNSEA) say that when orders stopped, many of their members turned to domestic work to earn income. For others, government-ordered shutdowns in the region have meant there was no income at all.

"Homeworkers are last in line to benefit from any help being provided by brands, manufacturers or governments," Janhavi Dave of HNSA told Anuradha Nagaraj in this Thomson Reuters Foundation article. "Many have not been paid since February and they are not expecting work for at least six more months."

Home-based workers around the globe have been organizing, and demanding that governments provide support as they are for other workers:

- HNSA’s Charter of Demands

- Home-based Workers Declaration: HomeNet Eastern Europe and Central Asia

- Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA) Appeal to Government

- COTRADO ALAC Declaration on the COVID-19 Pandemic and their May 1 message of solidarity on YouTube

- Open Statement about Impacts of Covid 19 Pandemic on Home Based Workers in Uganda

Garment Workers

In a joint statement, WIEGO, Asia Floor Wage Alliance (AFWA), HNSA and HNSEA called on brands to extend a one-time Supply-chain Relief Contribution (SRC) to all garment workers in their supply chains during the COVID-19 crisis. The crisis has revealed the scale of informality and subcontracting, including to home workers, that sustain global garment supply chains. Home workers have not received payments for work already performed prior to lockdown and, as the most vulnerable workers in the chain, are facing extreme hardship.

An estimated 60 million workers worldwide, based at home and in factories, make garments for local and international apparel companies. They are bearing the brunt of imposed lockdowns, border closures and supply chain disruptions.

- BLOG: The world’s most vulnerable garment workers aren’t in factories – and global brands need to step up to protect them by Marlese von Broembsen

In Vietnam, for example, garment workers say that they have lost work orders from Europe. An article in The Guardian reports on catastrophic cancellations for Bangladeshi garment workers: “More than one-quarter of the country’s 4 million garment workers have already lost their jobs or have been furloughed without pay because of order cancellations or the refusal of brands to pay for canceled shipments.”

Export garment workers in Bangladesh, and elsewhere, include not only wage workers in factories but also sub-contracted workers in their own homes. But articles and estimates on garment workers often do not take the sub-contracted home-based garment workers into account.

In a guest blog for the Ethical Trading Initiative, Janhavi Dave of HomeNet South Asia looks at what global and domestic brands must do to protect homeworkers, the backbone of the garment industry.

More:

- AFWA Statement of Demands for Garment Workers

- Clean Clothes Campaign blog: How the Coronavirus influences garment workers in supply chains

- Abandoned? The Impact of Covid-19 on Workers and Businesses at the Bottom of Global Garment Supply Chains by Mark Anner, Penn State Center for Global Workers’ Rights (CGWR)

Self-employed home-based workers lose markets

Home-based workers who are self-employed are also without income due to lockdowns. They cannot meet with customers or clients — or even, in countries like the Philippines where the shutdown is absolute, venture out for essentials like food.

Many were unable to stockpile raw materials before lockdowns began. They might not have had time, storage space or the available cash to do so. This prevents them from using this time in isolation to amass products that they can sell once the lockdown is over.

In many countries in Africa, home-based workers belong to self-help groups or cooperatives that rely on steady orders from brands and social enterprises. Now, cooperatives in Africa report that work orders have stopped. In Uganda, home-based workers say orders declined steadily from the beginning of 2020, especially for export markets. In Kenya all production for the export market has halted, despite pending orders, due to restrictions that hampered the collective production process.

Solidarity and adaptability

Organized home-based workers are proving the benefits of solidarity.

In Ethiopia, organized home-based workers have established a task force to raise awareness and educate members about prevention. Women in Self Employment (WISE) is augmenting government distribution of basic food and sanitation products to the most vulnerable households among their 19,000 credit and savings cooperative members.

In Uganda, groups that have joint savings initiatives were able to use the savings they had to stock up on basics when the lockdown was announced. Solidarity among members means the savings and stocks are shared to help those who are most in need.

In Bulgaria, home-based workers adopted an usual strategy - they sent their demands to officials accompanied by gifts of their wares, to remind the government of how important their products are to people, local economies and traditions. It worked. The Council of Ministers, the President, and the mayors of municipalities agreed to provide interest free loans and other supports. Learn more in this blog on home-based workers' innovations and adaptations.

Putting skills to work to make essential emergency gear

Some home-based workers have turned the COVID-19 crisis to their advantage by turning their valuable sewing skills into helping others survive, too.

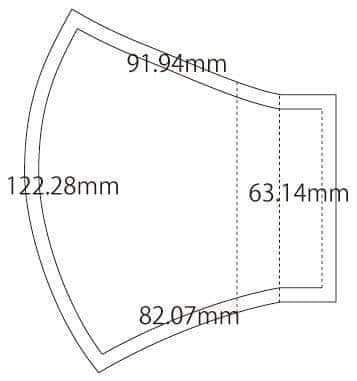

In Uruguay, Sindicato Unico de la Aguja, a union that organizes home-based workers, received an order for 30,000 masks from the union of police officers in mid-March. They expanded out from there, making masks for many others, and the government keeps adding orders.

In Kenya, the wearing of masks is mandatory, increasing the demand for them. Home-based workers with the requisite skills are producing masks for the informal market.

In India, SEWA Mahila Housing Trust has engaged home-based workers in making surgical masks and medical gowns to help with the medical relief efforts.

In Ethiopia, home-based workers are securing orders from the public health system and from NGOs for making masks.

In Cambodia, home-based workers are producing masks and using social media such as Facebook to sell their products.

Other organizations have also found contracts sewing personal protective gear. Now the HomeNet International (HNI) Working Group has added a demand in its statement to governments for home-based workers to be engaged by national governments, so their skills can help others, while providing needed income in this crisis.

Small spaces and added pressures

Home-based workers face other additional challenges at this time, though they are accustomed to working at home. When home is the workplace, and home is small and crowded, the new COVID-19 confinement policies mean even those who have work face competing uses and users for their workplace.

Many home-based workers live in very small, one- or two-room dwellings with many family members. Often, these are in slums or informal settlements where basic infrastructure — running water and sanitation, drainage and electricity — are inadequate or non-existent. This presents challenges at the best of times; in these worst of times, it means they must try to produce from crowded, unsanitary and inescapable confines.

Most home-based workers are women who face additional demands on their time for household chores, cooking and child care when all family members are sheltering at home. And since schools and child care centres are closed in much of the world, that work is without respite.

Health risks also proliferate in such confined spaces. If the work produces harmful airborne particles or fumes, the home-based worker and her family cannot escape out of doors.

- More about home-based workers