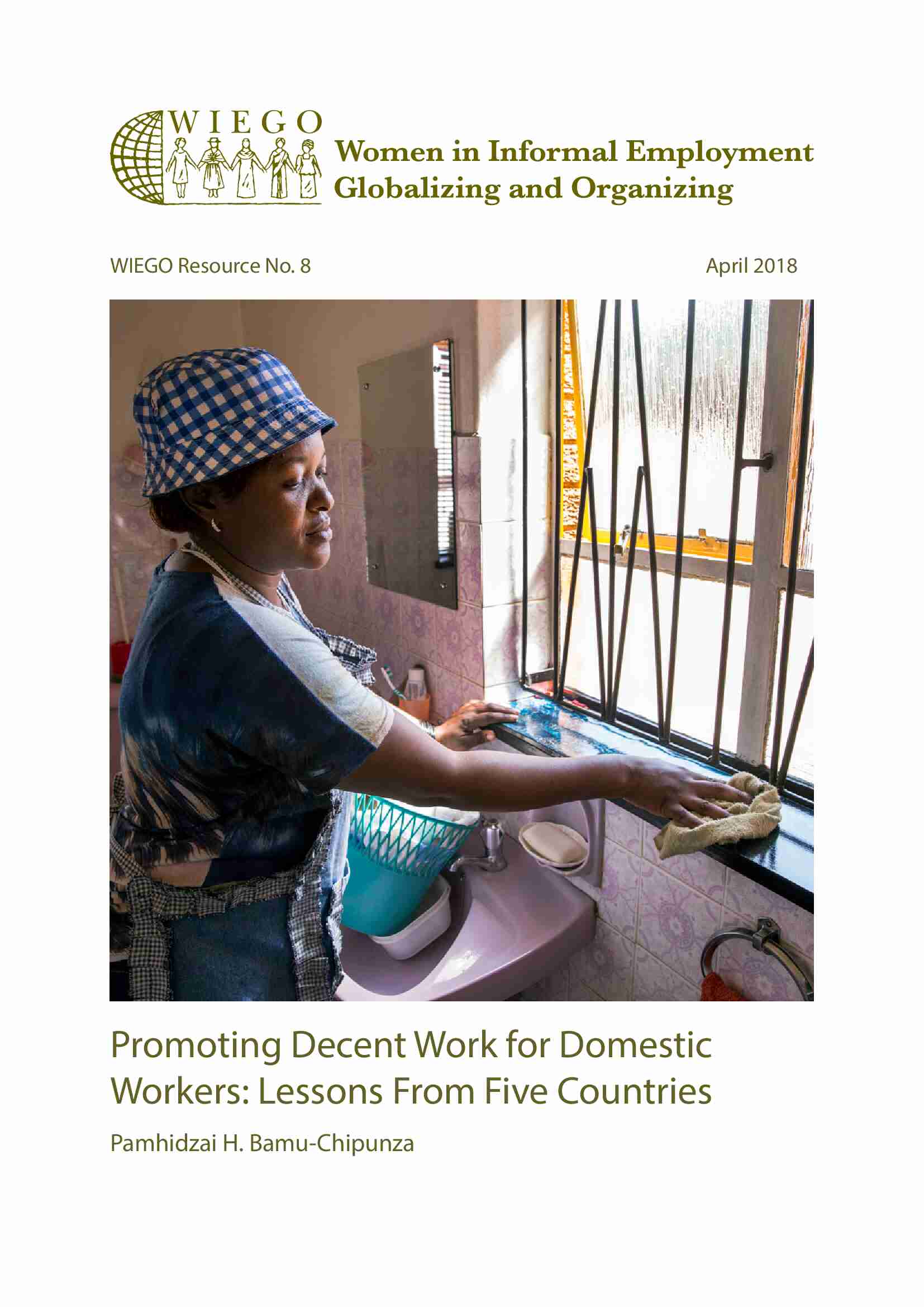

Domestic workers in the household often organize to form a line of defense against crime. Anna Nkobele, shown here working in her employer's home in Johannesburg, belongs to a community organization called Domestic Watch, which meets monthly to teach domestic workers to be aware and safe. Photo credit: Jonathan Torgovnik | Getty Images Reportage

Who Are Domestic Workers?Domestic workers provide a range of services in private homes: they sweep and clean; wash clothes and dishes; shop and cook; care for children, older people and disabled people. They provide gardening, driving and security services.

The almost 76 million domestic workers around the world represent 2.3% of total employment worldwide. They provide essential services that keep households working, yet most work in vulnerable situations with deep-rooted layers of violence and discrimination based on class, race, ethnicity or gender. Despite contributing to society, the economy and providing essential services, they are often excluded from legal and social protections. In several countries, households are not recognized as workplaces, and domestic workers are not recognized as workers.

Demand for domestic services is growing worldwide due to more women working outside the home, the aging of populations and the increasing need for long-term care and the loss of extended family support.

Domestic Workers & ILO Convention 189: Making it Real - Africa

Featured ResourceYour Toolkit on ILC Convention 189

WIEGO and the International Domestic Workers Federation (IDWF) partnered to write this toolkit to support IDWF affiliates in their efforts to make ILO Convention 189 real for domestic workers. This version is tailored to Africa and has focused on our activities in this region. In 2022, WIEGO and the IDWF adapted this toolkit for the Caribbean region.

Defining Domestic Workers

According to the International Labour Organization (ILO) Convention No. 189 on Domestic Work, domestic workers are defined as as “any person engaged in domestic work within an employment relationship.” Domestic work is defined as “work performed in or for a household or households.”

Statistics on Domestic Workers

Data in this section are also reported in Making Decent Work a Reality for Domestic Workers and Domestic Workers in the World: A Statistical Profile (WIEGO Statistical Brief No.32).

Domestic workers are identified in a specific category or categories in labour force surveys. However, in practice, those who work for multiple households or as child care or personal care workers, or are hired by or through service agencies, are often not captured as domestic workers. At the 20th International Conference of Labour Statisticians in 2018, the following statistical definition of domestic workers was adopted: “workers of any sex employed for pay or profit, including in-kind payment, who perform work in or for a household or households to provide services mainly for consumption by the household. The work may be performed within the household premises or in other locations” (para. 104). This definition is an important step in improving the measurement of domestic workers.

-

75.6 million

people aged 15 years and older in the world work as domestic workers.

-

81%

of domestic workers in the world work informally and have no effective access to social or labour protection.

-

76%

of domestic workers worldwide are women.

-

55%

of the world’s domestic workers are in two regions: East and South-eastern Asia (36%) and Latin America and the Caribbean (19%).

-

80%

of women in domestic work are engaged as cleaners and helpers.

-

1 in 6

or 17% of the world’s 76 million domestic workers is an international migrant worker.

-

7.1 million

children under the age of 17 work in domestic service.

Additional Information on Domestic Workers

-

Some live on the premises of their employer – 29% of women domestic workers and 23% of men. Most domestic workers are hired directly by a household, while a little over one-quarter are hired through a service agency. Others work part time and many have multiple employers.

Read More in Domestic Workers in the World: A Statistical Profile -

Worldwide, 36.1% of domestic workers are excluded from national labour legislation, and 50.1% have no legal entitlement to social security. However, in Chile, with a labour law that regulates private household work, rates of informality among domestic workers are much lower: 29% for domestic workers in Metropolitan Santiago, 41% in urban Chile and 48% in Chile nationally.

Access global statisticsView WIEGO's Chile Statistical Brief -

The majority of domestic workers are women. In developing and emerging countries, 79% of domestic workers are women and in developed countries, 64%. Globally, domestic work is 4% of women’s employment and 1% of men’s. In the developed countries of the Middle East, almost half of employed women are domestic workers in comparison to 15% of employed men.

Read More in Domestic Workers in the World: A Statistical Profile -

Across all countries, the overwhelming majority of women in domestic work (around 80%) are engaged as cleaners and helpers. Men in domestic work are engaged in a wider range of types of work: around one-third are security guards, gardeners and building maintenance workers; around one-quarter are cleaners and helpers, and a little less than one-quarter are drivers. Across the countries, around 7% of women domestic workers and 1% of men are engaged in direct care.

Read More in Domestic Workers in the World: A Statistical Profile -

Migrant domestic workers often live in the employer’s home, facing the challenges of both personal and economic dependency. Additional challenges include abuses in the recruitment system, such as excessive advance commission fees and wages and passports being withheld by the employer, and verbal and physical abuses and sexual harassment at the hands of employers or state officials. To protect migrant domestic workers, laws and regulations are needed at the international level and in both sending and receiving countries.

Read more in the ILO Report "Making decent work a reality for domestic workers" -

Children are particularly hidden and among the most difficult to survey. The informal employment arrangements in which they work exclude them from labour and social protections. Their isolated workplace makes it difficult for them to exchange with other children or seek help when they face problems.

Visit the International Domestic Workers Federation for Additional Resources

Domestic Workers' Contributions

Domestic workers provide services that are socially necessary for the maintenance of households and the well-being of families, most often in the form of either direct (face-to-face personal care) or indirect (including cooking, cleaning and other work that ensures a healthy and safe living environment) care activities. Millions of such workers play a central role in supporting the care needs of households.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted domestic workers’ crucial role in ensuring the health and safety of the families and households for which they work – from basic cleaning to personal care for children, older people and those who are sick. However, the pandemic also deepened pre-existing inequalities.

Driving Forces & Working Conditions

Many factors lead women to enter domestic work. Women from poor households or disadvantaged communities often have few employment opportunities and may face discrimination based on gender, caste or class, race or ethnicity. Cleaning, cooking and caring for children and the elderly is almost universally regarded as women’s work, so men rarely compete in this job market.

Most domestic work is informal: in many countries domestic workers are completely excluded from labour law and social security protection, or inferior standards apply. In Asia Pacific, the majority (61.5%) of domestic workers are fully excluded from coverage under national labour laws, while 84.3% remain in informal employment. Even where protective laws are on the statute books, they are frequently ignored by employers and not enforced by authorities.

Compared to most other wage workers, domestic workers tend to have lower wages, fewer benefits, and less legal or social protections. Very few domestic workers have labour contracts. They usually have no maternity leave, health care or pension provision.

-

Because domestic workers are employed in private homes, they are invisible as workers and isolated from others in the sector. Especially live-in domestic workers are economically and personally dependent and thus working on the good or bad will of their employers. Private homes can be “safe havens”, however, growing evidence suggests domestic workers are exposed to a range of unhealthy and hazardous working conditions.

Domestic workers often have a personal, intimate knowledge of their employers, but the relationship is highly unequal, leaving many domestic workers vulnerable to verbal, physical or sexual abuse. Often differences in race, class and citizenship increase this inequality.

Finally, a widespread perception that labour standards cannot be enforced in private homes means many employers do not comply and the government does not enforce labour laws regarding wages, benefits and working conditions.

-

According to the International Domestic Workers’ Federation, some domestic workers face multiple forms of violence: physical abuse, intimidation, threats, bullying, sexual assault, harassment, being provided poor-quality food and a lack of privacy. Severe instances of violence, including murder, have been documented.

The ILO Convention 189 on Decent Work for Domestic Workers was the first convention that stipulated governments’ need to ensure protections against all forms of abuse, harassment and violence. In 2018 and 2019, a delegation of domestic workers participated in negotiations at the International Labour Conference around violence and harassment in the world of work; they contributed to securing ILO Convention 190 on Eliminating Violence and Harassment in the World of Work. In this convention, domestic work is included in a list of occupations in which exposure to violence and harassment may be more likely and therefore requires specific attention of governments regarding protection and preventive measures.

-

In many countries, labour and social protection laws exclude domestic workers from their protections in whole or in part. Sometimes, domestic workers are covered by laws but not in practice because the laws do not cover their specific needs or are difficult to enforce. Many domestic workers do not know what benefits and protections they should get in exchange for taxes paid and contributions made. Migrant workers face particular challenges, leaving them with little legal protection, especially if they are undocumented or have been trafficked.

For resources on legal and policy challenges for domestic workers, see these resources:

-

Data on wages in domestic work are available in the ILO Bureau of Statistics Database for only a few countries. The data show that domestic workers receive substantially lower wages than other employees. They typically earn less than half of average wages – and sometimes no more than 20% of average wages. Domestic workers are frequently excluded from minimum wage protection. An estimated 21.5 million domestic workers do not fall under the minimum wage protections in the country in which they work. Those who are covered are often entitled to a lower minimum wage than other workers.

-

In some cases, domestic workers are hired by third-party agencies. The agency may see its role only as negotiating the placement, not overseeing working conditions. Often agencies act as employers without accepting the obligations that go along with this, namely, respecting labour rights, including providing for social protection.

Agencies increasingly operate through internet platforms and domestic workers are often only allowed to access the platforms if they register themselves as self-employed workers. The Danish trade union 3F negotiated the first-ever collective agreement with a platform company, Hilfr, in 2018 and this now has provisions including that all workers who use the platform are considered employees and links workers to union support.

Agencies play a crucial role in connecting domestic workers with work when they seek employment in foreign countries. These agencies have sometimes been linked to criminal activity. Article 15 of the ILO Convention 189 clearly spells out the conditions and regulations that need to be in place to respect the rights of domestic workers.

Policies & Programmes

Effective policies and programmes are crucial for improving the rights and conditions of domestic workers. These measures can provide legal recognition, social protection and fair labour standards.

-

In 1948, the International Labour Conference (ILC) recognized the need for a special international instrument for domestic workers. For decades, however, no such instrument – convention or recommendation – was introduced.

That began to change in 2007, when domestic workers and support organizations from around the globe met for the first time in Amsterdam. A coordinated global effort led to the adoption of the Convention Concerning Decent Work for Domestic Workers (C189) and accompanying Recommendation at the 100th ILC in Geneva in 2011. The ILO tracks the number of countries that have ratified C189.

For more information, read the Campaign for a Domestic Workers’ Convention and “Yes We Did It!”. In 2021, WIEGO and IDWF reflected on the victories and the challenges that remain.

Play Video

Play Video

C189 Conventional Wisdom

-

ILO Convention 189 has been ratified by 38 countries. Implementation measures include

- a Magna Carta for Household Helpers in the Philippines, a subsidized state scheme with collective bargaining in France, Belgium and part of Switzerland, and an increase in minimum wages in Guinea. In Peru, a 2020 law explicitly provides for mandatory social security coverage for domestic workers, and in Costa Rica, a system forsocial security registration of part-time domestic workers has been introduced.

- Some countries – including Ghana, Hong Kong, Tanzania, Togo and 10 federal states in the US – that have not ratified the convention have introduced laws, policies or other measures to protect domestic workers and regulate the sector.

Organization & Voice

The global movement towards an ILO Convention for domestic workers followed by C189 ratification campaigns provided a tool for domestic worker organizations to organize and take action to improve domestic workers’ working and living conditions. In 2013, the International Domestic Workers’ Network transformed itself into the first global union organization run by women: the International Domestic Workers’ Federation (IDWF).

The IDWF has 88 affiliates from 68 countries, representing over 670,000 domestic workers. IDWF affiliates are organized in trade unions, associations, registered groups and workers’ cooperatives.

In 2017, WIEGO and the IDWF partnered to establish the C189 and Domestic Workers: Making it Real project to provide training and technical support to IDWF affiliates in Africa and the Caribbean to enable them to demand ratification and the enactment and implementation of laws and policies that protect domestic workers in line with C189. This would empower their domestic worker members to defend their rights and assist them in resolving labour disputes.

We also collaborated with IDWF affiliates in South Asia to document the provision (or lack thereof) of social protection to domestic workers and develop policy recommendations to improve their situation. This work aimed to empower organizations of domestic workers to integrate social protection concerns into their organizing and bargaining strategies.

Since 2021, WIEGO has collaborated with the IDWF in Africa to co-design a legal empowerment training programme that equips domestic workers with the knowledge and skills they need to be able to offer paralegal services through their organizations.

Amid great progress, most domestic workers are not organized into trade unions and have no representative voice. In some countries, they are not allowed to organize or to join trade unions. Even where they have the legal right to organize, it is difficult because they are isolated and vulnerable. The nature of the worker-employer relationship and the lack of sector employer organizations as bargaining counterparts makes it difficult to engage in collective bargaining with employers.

Read more about efforts to organize domestic workers in the 2012 book The Only School We Have: Learning from Organizing Experiences Across the Informal Economy (pages 28-41).

More Occupational Groups

-

Garment Workers

Learn More -

Home-Based Workers

Learn More -

Street Vendors

Learn More -

Waste Pickers

Learn More