Findings from South Africa suggest that supporting informal employment could help countries reach development goals

by Mike Rogan & Paul Cichello

Informal workers are all too often seen simply as “vulnerable” and “unproductive” workers trapped in a cycle of poverty. It’s true that informal workers – from street vendors to waste pickers to domestic workers – often struggle to make ends meet: of the roughly 839 million working poor in the developing world that survive on less than $2/day, about 80 per cent are in the informal sector. However, the poverty narrative ignores what this income provides daily to working individuals and families: money for food, housing, health needs, and schooling. And there seems to be very little research to tell us how informal employment contributes to national development goals such as poverty reduction.

A better understanding of the role of informal employment in actually reducing poverty – rather than perpetuating it – could influence a new generation of policies that recognize and support the role of earnings from informal employment in the households of the working poor. This is an important consideration since progress in reducing working poverty (that is, poverty among the employed), particularly in developing countries, has stalled over the past five years.

To explore this idea further, we analyzed household survey data from South Africa to investigate how earnings in the informal economy are reducing the country’s poverty rate. South Africa, a middle income country where only about a third of the workforce is in informal employment, is an interesting case because it is one of the few countries in sub-Saharan Africa in which informal employment comprises a smaller share of the workforce than formal employment. As a result, the way in which informal earnings keep workers and their households above the poverty line is somewhat obscured by the large and dominant share of both the workforce and household income from formal employment. Even with a relatively small aggregate contribution to total employment from the informal workforce (again, roughly a third), the importance of informal earnings to poverty reduction is evident.

The informal economy and working poverty in South Africa

The importance of social grants and informal employment

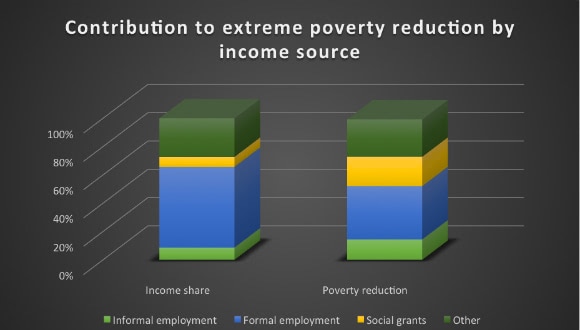

Household income data can be deceiving. A look at the numbers simply reflects the fact that individual earnings and household incomes are often very low in the informal economy. Without contextualizing the impact of these earnings, a first glance at the distribution of household income in South Africa in the figure below shows that the vast majority (57 per cent of all household income) is attributed to “formal” earnings and relatively little income flows into households from social grants and informal employment, 7 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively.

However, when it comes to the impact of these same income sources in terms of their contribution to reducing poverty in South Africa, the link between informal employment and poverty reduction is revealed. In particular, when the focus is on reducing extreme poverty, defined as the point at which households are not able to meet even their most basic food needs, income from social grants and informal employment becomes much more important.

For example, while only 7 per cent of household income comes from social grants, just over a fifth (21 per cent) of that household income – which currently keeps households above the poverty line – comes from social grants. At the same time, earnings from informal employment account for 14 per cent of income that keeps households above the poverty line, even though those earnings account for only 9 per cent of total household income. Meanwhile the contribution of earnings from formal employment decreases from 57 per cent of all household income to 38 per cent of income that keeps households above the poverty line, i.e. 38 per cent of the total contribution to poverty reduction.

So, while formal earnings are still the single largest factor in reducing poverty, social grants and informal employment are actually more important relative to their overall share of household income. This is an important finding for policymakers because it highlights the role earnings from the informal economy contribute both to households and to poverty reduction at the national level.

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS).

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS).

A closer look by type of employment

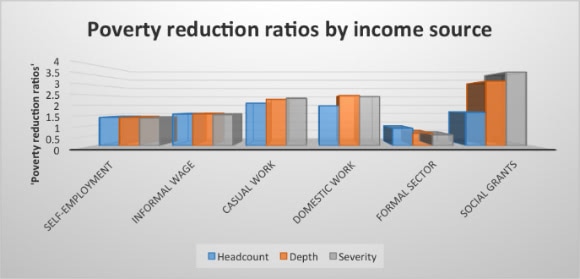

Perhaps a clearer way to highlight this link is to estimate ratios of “poverty reduction” where values greater than “1” indicate that an income source has a larger contribution to poverty reduction relative to its contribution to total income. The graph below disaggregates these ratios by the types of employment (including the informally self-employed, informal employees, casual labourers and domestic workers), which are captured in the South African data.

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study.

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study.

According to these categories, the informally self-employed operate enterprises which are not registered for income tax or value-added tax. Informal employees are those in regular employment but who do not have work-related social or legal protection. Casual labourers are a separate group who do work that is irregular and short-term in nature. These categories are not necessarily comparable with the international classification of informal employment derived from official Labour Force Surveys (and endorsed by the ILO), but the advantage is that the household survey from which they are derived also measures total household income, which, in turn, can be used for poverty measurement.

For a fuller picture of how the earnings of each of these categories of informal workers contribute to poverty reduction in South Africa, ratios for the reduction of the poverty headcount, the depth of poverty and the severity of poverty are presented together in the graph. The poverty headcount is the most widely used indicator by poverty researchers and is simply the percentage of households which are poor. Since there is very little difference between a household that is one dollar below the poverty line compared with one that is one dollar above the poverty line, the depth of poverty (or the poverty gap) is an indicator which complements the poverty headcount rate by measuring the average distance of the poor below the poverty line. Finally, because we are often interested in focusing on the poorest households, the severity of poverty (or squared poverty gap) is simply an indicator which gives additional weight to households which are far below the given poverty threshold.

Findings reveal clear connection to poverty reduction

The clear finding is that all sources of income except formal employment earnings are relatively more important for poverty reduction than their absolute contributions would indicate. For the self-employed in the informal sector, the ratio between the contribution of their earnings to poverty reduction (at all three measures) and the overall share of income is about 1.4. In other words, their contribution to poverty reduction is about 40 per cent higher than their contribution to overall household income.

Casual work and domestic work are particularly important to reducing poverty in South Africa. Their poverty reduction ratios are all two or greater and they increase as the measures of poverty become more sensitive to households further below the poverty line (i.e. the depth and severity). In other words, the importance of these two types of informal employment are twice as important to keeping households above the poverty line (or at least closer to it) than a glance at their contributions to total household income would suggest.

Earnings from all types of informal employment (and social grants) are, therefore, relatively potent contributors to poverty reduction. If policymakers are not made aware of this, then the role of informal employment to national poverty reduction targets would be almost completely obscured by a focus on low earnings in the informal economy.

“Per job” impact revealing for extreme poverty households

Because two-thirds of employment in South Africa is formal and because earnings from formal employment are far higher than those from informal employment, it is not surprising that, at the aggregate, formal work has a larger absolute impact in reducing poverty. While we long for the day when all South Africans can enjoy secure jobs with earnings levels well above the poverty line, we should not denigrate work that brings those with very low incomes up closer to or just above the poverty line.

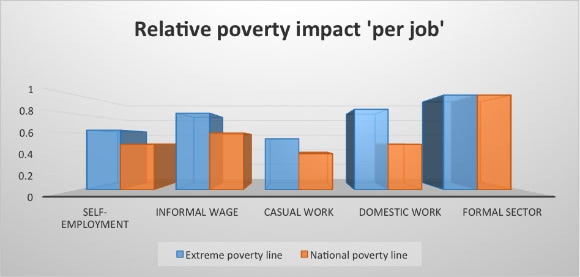

In order to illustrate this point, the graph below depicts the “per job” impact on poverty of each employment category relative to a formal job at the extreme poverty line and the national poverty line. The national poverty line is higher than the extreme poverty line and is defined as the point at which household can meet their basic food needs but not necessarily their non-food requirements (clothing, shelter, etc.).

The first thing to notice in the graph is that all informal jobs have a smaller poverty impact than formal jobs, but this is, again, because earnings are so much higher in the formal sector. The more revealing finding is that, at the extreme poverty line, a job in informal self-employment has 63 per cent of the poverty-reducing impact that a formal job has. Put differently, eliminating 100 informal self-employment jobs, as some government policies have sought to do in order to discourage “illegal trading”, would drive as many households into extreme poverty as eliminating 63 formal jobs. It is precisely these types of stark comparisons that are made possible when the focus is switched to the contribution of informal employment to poverty reduction.

Moreover, informal employees and domestic workers have a “per job” impact on poverty reduction, which is much closer to a formal job (81 per cent and 85 per cent, respectively). In other words, eliminating these jobs is almost the same as eliminating formal jobs. So it is the ability of these types of employment, despite their low earnings and difficult working conditions, to keep households out of poverty that makes their contributions so significant.

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study.

Source: Own calculations from the National Income Dynamics Study.

Policymaking that rethinks the role of informal employment

What do these findings mean in terms of development goals? The most immediate implication is that, if we are serious about reducing working poverty in developing countries, then protecting the earnings and working conditions of workers in the informal economy has to be a priority. The South African example is important because it demonstrates that, even when informal employment is overshadowed by a large formal sector, the role of informal employment in reducing poverty is crucial. For other developing countries where informal employment forms a larger share of the workforce, the role of informal jobs in reducing poverty will likely be even more prominent.

One key problem, however, is that many countries do not capture data on total household income (in order to measure income poverty) and status in employment (e.g. from Labour Force Surveys) in the same national survey. A clear recommendation which stems from our research is that, as countries work towards developing comparable indicators of working poverty, they should also strive to collect data that highlights the impact of informal employment on national poverty rates.

Without analyses that highlight the role of informal employment in reducing poverty, the perception will remain that informal employment is not a viable solution to poverty reduction because it is, by nature, low paid and does not offer social and legal protection. We argue, however, that if policymakers understood the importance of earnings from informal employment to keeping many workers and their households out of poverty, policies concerned with informal employment may look quite different.

Notably, protecting the earnings and livelihoods of informal workers addresses directly three of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In other words, since working poverty is a central feature of overall income poverty in most developing countries, the goals of reducing income poverty (SDG 1) and achieving decent work for all (SDG 8) cannot be met without addressing the challenges faced by informal workers in pursuing their livelihoods. Moreover, since women who work are more likely than men to work in informal employment and in jobs which are the most vulnerable, protecting earnings in the informal economy is a crucial strategy to achieve gender equality (SDG 5).

Photo by Asiye eTafuleni.

This research was funded by the South African National Treasury through the REDI 3x3 research initiative.